There used to be a party game ‘Name three famous…’. Ask the public to name three famous tunnellers. Readers of this magazine could probably do so – we have interviewed several on these pages, and there are also historical figures from the early days of tunnelling whose names are known – but those outside the tunnelling community would almost certainly be stumped today. None are widely known to the general public, and especially so internationally – until now.

Arnold Dix is that tunneller. As President of the International Tunnelling and Underground Space Association (ITA) he will be giving the headline address at the organisation’s conference next month, in China. He is also a barrister, whose first employment was for a law firm in Melbourne, Australia. His company ALARP – it stands for ‘As Low As Reasonably Practicable’, referring to reduction of all kinds of risk – describes itself as assembling expert groups to assist in ‘complex legal/ technical/scientific matters in the area of major infrastructure safety, risk and the environment…. always focused on complex problems and issues that demanded bespoke outcomes.’ Whether that makes it a legal company or an engineering company is anyone’s guess. He is also a Professor of Engineering (visiting – at Tokyo City University) and a specialist in disasters – especially tunnelling disasters, and in underground fire safety – who is frequently called in to analyse and advise.

“That started with the Twin Towers collapse in the US, when I looked at the tunnels under the World Trade Centre and how they performed,” he says. “And then I did the London bombings, Madrid bombings, Hong Kong bombings, tunnel collapses in the Gulf and in Australia, fires, explosions… I’ve done quite a bit.”

Oh, and he was also the front-man and chief foreign adviser for the rescue in the Himalayas of the 41 tunnellers trapped in late 2023, when a landslide hit during tunnel excavation of the 4.5km-long Silkyara Bend- Barkot road project in Uttarkashi district of Uttarakhand, north India. The road tunnel is intended to connect important Hindu pilgrim sites in the region.

The rescue was successful. Not a single man died or was injured. It took 17 suspenseful days and it gripped the world’s attention. Each evening Arnold Dix explained, on TV and video and social media, the progress, the problems, the prospects for the rescue and the men. Bearded, in hard hat and high-vis jacket and Australian accent he radiated calm and confidence and reassurance to all who watched, which was a large proportion of the world; and the world – and India in particular – was thankful.

It made Arnold Dix the world’s most famous tunneller of the current time. In India he is more than that: he is close to a superhero. More of that later.

But is Dix actually a tunneller at all? Or is he a lawyer, or a fixer, or an engineering analyst or none of those? Or…?

“I’m all of them,” he says. “That’s part of the challenge for me. In an age where everybody is meant to just do one thing I’m more like a Renaissance man from the Middle Ages. I don’t claim to be the best at anything, but I am pretty good at a range of things. So I’m pretty good as a lawyer, and I’m pretty good as an engineer and I’m pretty good as a truck driver and I’m pretty good as a welder. But mostly people only know me for one of those things. If someone knows me as a tunnel ventilation person I don’t tell them that I drive trucks.

“Or if I’m doing a fire- and life-safety thing I don’t tell people that I also do structural fault analysis because people compartmentalise and it upsets them. I keep quiet and just kind of do whatever I need to do. So it’s a bit odd.”

We spoke, by Zoom, on a Friday evening his time in Australia, but it was by no means his last engagement of the week. “People in America ring around now because it’s good for their time-zone. Then the Europeans, then the Africans. It will be midnight before I call it a day.”

Driven, active, whatever you like to call him, he still presumably finds weekend time for what he calls the “least successful flower-growing business in the area,” on his small farm in Monbulk, about 50km out of Melbourne, where he also grows fruits and keeps donkeys and emus.

To get his recent fame out of the way first: How did he become the frontman for the Himalayan rescue? Was that through ALARP or through the ITA or because he’s a tunnel expert or a disaster expert?

“The reality is it’s because they knew me. Within governments around the world I’m known as a guy you can call confidentially, and I provide advice and I’ve been doing that for virtually all my career. And so I was known to the Indian government because they know I do disasters, just like I’m known to the Americans, like I’m known to the Australians, like I’m known to the UK, but it’s just that when I do it normally it’s confidential so no one talks about it.

“So, for example, I’m a member of the Association of British Investigators but no one knows that. Why would I tell them? Until just a few weeks ago I was retained special legal counsel to one of the world’s largest law firms and concurrently I am in updating discussions on… some tunnels but I don’t talk about it; it’s just something that I do.” Similarly, he did reviews of other tunnels. “But you never will have heard of me because these things are done confidentially so I just quietly do my thing.

“And, even though I am President of ITA, a lot of people in ITA don’t know what I do, they just know that I’m the President so I must obviously be doing something.”

His job, whatever it is, would seem fairly unique, which he concedes. “It almost is a bit mysterious. I don’t really promote myself. I usually say to people that they’ll know when they need me.

“Typically what happens is there’s a bit of a problem and someone will call me and say ‘Can you help?’ And if I can, I do.”

When the problem in the Himalayas emerged, with tunnellers trapped underground by a local collapse, his first utterance to the public, almost as soon as he reached the site, was: ‘41 guys will be out by Christmas.’ It was reassuring, which was wonderful; but it was a hugely confident thing to say. Was he giving himself to be a hostage to fortune or did he believe it then, and later? Were there times when he thought it was not going to happen?

“Now what I’m going to say doesn’t sound like me, the responsible scientist-engineer; but I just had a feeling that we were going to be able to do it even though I didn’t know exactly how.

“I knew partly what the causes were, but I did know the one thing that was really important to me, which was that no-one had been hurt in the first instance. And I thought that was a really good sign. I also knew that there was air and the ability to get food and medicine to them; and so I thought those also were really good signs.

“And so, in combination, I thought, ‘Look, there’s no one dead yet. And if we’ve got the ability to keep them alive, this is already extraordinary, we’re already halfway there.’ I have never had that circumstance before. Always before when people call me, people are dead. So this on the face of it was already looking not like a disaster, it was looking like a rescue. I felt quite empowered by that. The schoolboy in me was like: ‘Okay. I’ve got a problem, but it’s not a situation which is already catastrophic, it’s a problem that I can make catastrophic by bad decisions or that I can resolve with better ones, so I’m up for this.’”

He was, so to speak, in the middle of training for it.

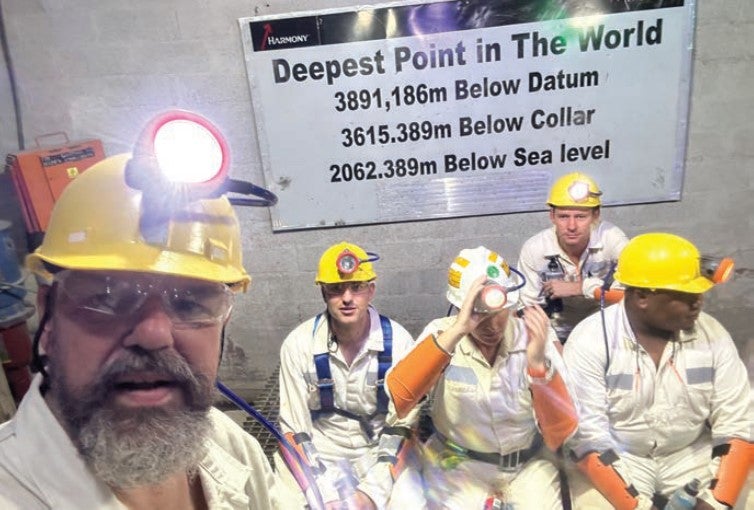

“It came at what was to be the end of a world tour,” he says. “I’d started in Africa by going down the world’s deepest goldmine, looking at how they were managing convergence at 4000m below the ground. I’d never been that deep before. And so that was really fresh in my mind. I’d then gone across to Scandinavia, to both Sandvik and Normet, just seeing the latest technologies that they have in terms of ground stabilisation, digital technologies and everything. I’d been to a lab in Helsinki looking at the latest performance of rods and rock bolts and all that sort of stuff. I’d been to the Colorado School of Mines and given a couple of lectures and looked at their research for extreme tunnelling and also at their outer space programme, so their robotics and everything. I’d been to Herrenknecht, to presentations on their latest technologies, and I’d met with their engineers, I’d been to their labs; and, I was actually at Herrenknecht when the first phone call from India came and I gave the first advice.

“So actually I was already on a crash course in the most extreme tunnelling stuff in the weeks before I got the call to come to India. It wasn’t like I was sitting at home mowing the lawn. When the call did come I couldn’t have been more prepped.”

He is also a barrister. Do the two jobs require the same set of skills?

“For the Silkyara incident the synergies just screamed out,” he says. “If I was prepared intellectually for the technical issues by my journey in the weeks before I was called to Silkyara, my legal expertise was absolutely required because sitting around the table were a group of top technical decision-makers. The heads of the Army and the Air Force, the Prime Minister’s department, the Uttarakhand emergency services – the list is huge. And, because the Indian legal system is similar to the Australian, the British, and the American, with their heritage in codified Common Law, I am hypersensitive to the roles and responsibilities of decision-makers and how to make operational decisions in a way that doesn’t expose you to prison or worse.

“Collectively we were making decisions which, on any view, even a child’s view, could at any moment have killed or contributed to the deaths of the people who were trapped or of rescue workers. An environment like that typically stops people making decisions because everyone gets a bit paralysed; but because I’m there as an informed and technically competent tunneller who happens to also be a senior lawyer it meant that we could make decisions with confidence: we knew that if there was an inquiry into our decisionmaking process we would stand scrutiny.

“Part of that is that we acknowledge that we had imperfect information. We would adjust our strategy as more information came to hand. We wouldn’t pretend that everything was going well. For example, we thought ‘If we use more torque on our augur, things are going to go better.’ They didn’t. The auger broke. So we could, a) pretend we hadn’t noticed; or b) we could blame the auger manufacturer; or c) blame the operator; or d) rethink our strategy. So we’d rethink our strategy without blaming whoever it was who had made the earlier decision; and that would put us, in a legal sense, in a very reasonable position as engineers responding to a real emergency, knowing that we could make the wrong decision. So long as we made the wrong decision for all the right reasons we would be okay.

“And I think that made a very real and tangible difference to the team – because it was a team thing. And I think that probably one of the key things I brought was this confidence in taking action, knowing that we had imperfect information and that lives were in the balance, and that our actions could make the difference between life and death.”

Going back a bit, how exactly did we get to here – being a leading expert simultaneously on law and on tunnelling safety?

“Firstly, I did geology at university, and then law; so although I’m a professor of engineering I’m actually a graduate not of engineering but of geology and mining geology. My postgrad work was in a mine, not doing specifications on a beam or something. I have worn the hard hat underground.

“And I’ve always, even from a little kid, had a love of the ground and rocks. That probably arose from when I was in primary school. I was in a part of Australia near the Snowy Mountains hydro scheme, and so I was exposed to some of the old blokes who’d take me and show me the tunnels and where they did the geological works and stuff. I thought that was very exciting; and they talked about the mountain in terms of the rocks being alive and how they behaved and that they weren’t just rocks. And that got to me: I am actually primarily a rock guy. And then I got into law and I discovered I was really good at law as well; and so my legal career is a real legal career and my technical career is a real technical career. And that’s the confusing part for people.

“I publish in technical tunnelling journals and I publish in legal journals; and also I work on contractual stuff.” He reaches to a crammed bookshelf behind him to produce a thick paper-bound volume, which is the standard FIDIC contract for underground works. “That’s originally my project. I went to FIDIC with the suggestion that we do a joint project between FIDIC and ITA, and now this contract is used by the World Bank for hydro projects.

“It is all about ground conditions; so that’s an example where the lawyer in me does something really helpful for the engineers. But then in another breath I’m one of the authors of the Handbook of Tunnel Fire Safety. It all makes sense to me.

“And when I’m talking to children now about the Silkyara rescue, one of my messages to them is ‘Try not to be too worried about what people tell you you’re going to be. Instead think about what you like, and how you imagine you might be.’ Because for me, I don’t have a problem at all about the fact that I do hands-on geology stuff and I do really esoteric, highest level contractual things. They are just tools in a toolbox. And I actually don’t understand how my rock hammer is so different to my pen – they are both just tools, both just connections between my head and the world around me.

“But I do realise it startles people, so I play it down a little because I don’t want to upset people. Last year the Americans gave me an award for my contribution to fire engineering for the world in tunnels. That’s cool. But imagine how my lawyer friends feel when they discovered that. ‘How did that happen? Because he’s a lawyer, right?’

“I am only confessing all these things because suddenly people are interested, which is new. What happened at Silkyara has kind of put a light on me and people are going: What the hell? What is he ?

“And, you know, the Prime Minister of my country stopped Parliament and thanked me by name on behalf of the Australian people. And the Leader of the Opposition said something nice as well; and when I saw that I thought: ‘This is so ridiculous because no one ever talks about tunnellers. Clearly I’m in a death sequence and weird things are happening in my head, or I’ve been run over by a truck and having a reaction to anaesthetic or I’m on party drugs and someone has spiked my drink.’ Because for technical people that doesn’t happen.

“And I’m still a bit not sure, because it seems it does all seem a bit surreal. I had 100 million hits on one of my videos in India. I don’t even know what 100 million is. It’s one in fourteen of the population of India. And I don’t really understand what that means.

“In India, I can’t walk in the street because people mob me. In a hotel I can’t get from my room to where the food is, because I get mobbed.” He has become a meme: “Children play dress-up, they can be Spider-Man, or Superman, or they now can be Professor Arnold Dix in a little yellow hat and a little beard and an orange shirt. It’s kind of nice, I suppose, but it’s a bit weird. I mean, what’s going on?”

Let us return to earth and to his day job. “In tunnelling disputes my advice is try to avoid the law, always. Come to some amicable arrangement. And that’s one of the things about that FIDIC contract. It has a focus on early identification of problems, not of disputes. Suppose ground conditions aren’t as expected; the support isn’t performing as we want it to; something unexpected is happening. That’s a problem. So have a process, a mechanism, between the parties’ technical gladiators, not their legal ones.

“Technical people just love solving problems. You know that. I know that. If we’re given a chance we just want to fix the problem. And it can be very simple fix, like ‘Turn Switch Number 2 to green’ or ‘Put in a bit of soil additive.’ Whereas lawyers love disputing problems, which is something quite different.

“A lot of my work is knocking people’s heads together saying ‘Don’t be so silly, do this, press button B and then it’ll be resolved.’ And it goes unnoticed because I am so not interested in having a public dispute, and because I’m absolutely convinced that the best people to solve underground problems are the underground technical people. So that’s what I do, and that’s what I’ve spent my career doing: helping resolve problems quietly.”

“That’s the sort of space where I’m in. I’m saying: ‘Come on, let’s be reasonable about this. We’ve got major infrastructure. We need to deliver it safely. We need to do it for the benefit of the environment, for the people, and let’s not be childish about it, let’s be professional…”

Being professional about things, he is to chair the ITA conference in Shenzhen… perhaps as you read this.

“We’ve got two big agendas. First we are trying to reorganise the ITA for the next 50 years, so there is a big reform agenda there. We have implemented succession planning and actual succession in key parts of the organisation.

“The other reform is about our activities – things like sustainability, how we articulate, how we enhance the performance of our underground infrastructure with the sort of demands that are upon us in the modern world.

That’s a big focus of accelerated work at the moment at ITA.

“We’ve got a big agenda on diversity, inclusion, and discrimination – I am male, and old, and white, which is a no-no for all of that, but I won’t be around forever. We’ve got a new team looking at our organisation: not just what we do, but how do we measure it, how do we judge ourselves, in what ways can we behave better? That’s really important for us, and it’s new. Add that we have individual memberships now for ITA – that’s also new. It means we have changed our whole membership strategy, at the same time maintaining the central importance of our member nations. So that’s a that’s a big change.

“And tunnellers have to go on doing their bit towards saving the world.”

And of his new-found fame?

“I think Silkyara and its happy result have been fantastic in making the world see that tunnellers are relevant, and that we are actually nice and we look after each other.

As a profession we are decent, we help each other.

You know I think that’s been really wonderful for us as a global industry, because I don’t think anyone would normally think about us at all.”